Student Guide to Phishing Attacks

Hackers and scammers use a continually evolving set of tools to break through computer security. One of the primary modes to get access is phishing, or sending fake emails from speciously reputable companies in hopes of gaining access to credit card numbers, bank accounts, or other sensitive information.

The term phishing was coined by a group of hackers in AOHell, a Usenet newsgroup, back in 1996. They had created an algorithm that generated fraudulent AOL accounts through fake credit card numbers. That group of hackers also impersonated AOL employees through their instant message service, asking users to verify personal information to confirm the their identity—thus fishing for information.

According to Phishing.org, the use of “ph” in the term is attributed to some of the earliest hackers being called “phreaks.” These (sometimes malignant) pioneers engaged in phreaking, or exploring and studying the telecommunication systems.

In 2001, phishers turned their attention to online payment processors. By 2003, scam artists had registered dozens of domains designed to look like major websites such as PayPal and eBay, among others. After creating these sites, phishers sent spoof emails to lure customers to login into the website and update their payment information. By 2004, attacks on banking web pages proved to be successful, and pop-up windows allowed scammers to gather sensitive information from victims.

These days, social media use is ubiquitous throughout the world and phishing scammers now have countless channels to attain access to victims. Deceitful emails and social media messages typically threaten a user with losing a privilege or entice them with a reward. Despite the advances in hardware and software over the past two decades, phishing schemes still boil down to one central concept: tricking visitors into revealing personal information. Once supplied, this info can be used to spread computer viruses, steal identities and financial information, create fake online personas, and much more. Notably, TechTarget (June 2016) interviewed Bryan Sartin, the managing director of the Verizon RISK Team and co-author of the Data Breach Investigations Report; Mr. Sartin found that 98 percent of data breaches are the result of human error.

This article explores how to identify the seven elements of phishing emails and what students should do following an attack.

Dead Giveaways of Phishing Emails – How to Identify a Phishing Attack

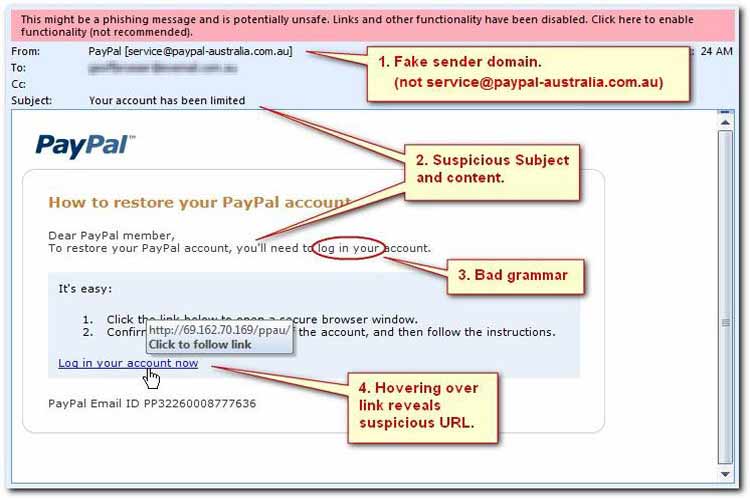

Phishers use a few common methods to reach out to potential victims, and it’s important to learn the red flags. Again, phishing messages are designed to look authentic—using logos, spoofed domain names, and the formatting of a reputable organization. To avoid falling prey to these traps, here are seven common indicators of phishing attempts.

Mismatched Links or URLs

Through hyperlinking, scammers may hide traps in innocuous-looking links or URLs. The email below appears to directly from Amazon, but by hovering over the link—not clicking it—the correct destination of the link pops up: redirect.kereskedj.com.

Pharming: Misleading Domain Names in URLs

Scrutinizing a message’s source also can save potential victims. Another trick involves including real and trustworthy-seeming web addresses to lull users into a false sense of security. English reads from left to right; therefore, presenting a reliable source such as Paypal in the beginning of a sender’s email can seem legitimate on the surface. It’s important to add that the vast majority of reputable URLs start with HTTPS. The ‘S’ stands for secure, meaning information on the site is encrypted, and links from HTTP sources should be treated with extra caution.

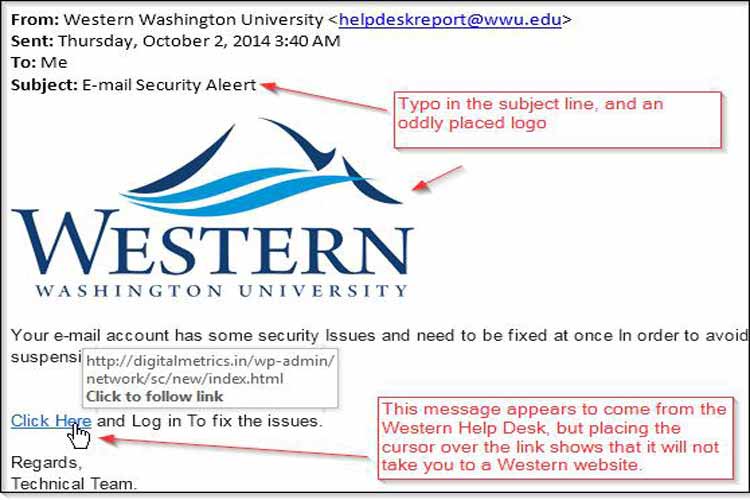

Bad Grammar and Poor Spelling

Not surprisingly, spelling errors and unusual grammar are also indicators of phishing attempts since established companies and universities rely on educated communications departments who rarely make these types of mistakes. If there is an error in the subject line or sentences read awkwardly, do not click.

Requests for Personal Information

Any emailed requests for personal information should be deemed suspicious. Students should never provide this info unless they know and trust the sender. Personal information includes usernames and passwords, credit card information, social security numbers, and answers to common security questions (e.g., city of birth, mother’s maiden name).

Requests to Front Money to Cover Expenses

Most students have heard of schemes involving a wealthy Nigerian prince looking for help to transfer money into the United States. A version of this email claims the prince needs to get $40 million from oil contracts and cannot use the country’s banking system—thus requiring the victim’s help and bank account number. Other schemes involve massive inheritances, large unclaimed prizes, or similar promises of money in exchange for access to one’s personal information.

Overall, students must use common sense and avoid random solicitations.

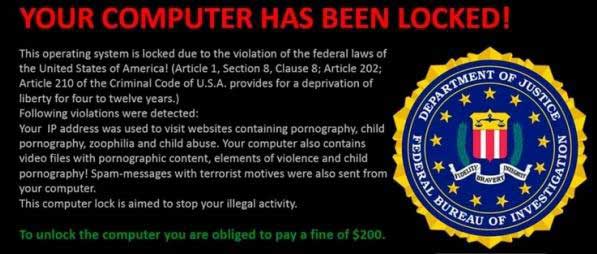

Aggressive or Threatening Tones

To generate a sense of urgency, scammers may use scare tactics to convince people to part with either information or money. Typical claims include a compromised bank account, an email account that is over capacity, or other time-sensitive requests. The statement may be followed up with threats about suspending or canceling the accounts if the information isn’t received immediately. Before responding via email or clicking supplied links, investigate the sender using some of the tips covered above.

While not specific to email, TechRepublic tells of one attack focuses on scaring a victim with a threat alleging the FBI has locked the victim’s computer requires a $200 fine to unlock it.

Do not rely on the information provided in the phishing email, as it might be set up by the same people attempting to extort money. Instead, call trusted internet service providers or campus IT personnel and deal with the issue.

Spear Phishing: Targeted Phishing Scams

Occasionally, attackers research their victims in advance, crafting tailor-made messages using a university or company logo and other relevant details. They may include generalized requests typical of a school or company with a link or document, claiming these files are attached to explain the request. Again, if unsure about the source of an email, ask a member of the IT staff for assistance.

What to Do After Being Phished

In a 2016 phishing test at Intel, 97 percent of users failed to identify phishing emails. Using the tips above can prevent students from falling prey to most phishing scams, but people make mistakes. In addition to contacting campus IT services, here is what students should do if they’ve fallen prey to a phishing scheme:

- Take the computer offline. If the device is connected to wifi, try disconnecting from the network. If this fails, turn off the wifi router. Disconnecting from the internet reduces the probability of infecting other devices in the same network with malware.

- Backup all files on the hard drive. If backing up data is routinely done, it is only necessary to backup new files. Focus on capturing all sensitive data and irreplaceable files such as videos and family photos.

- List the information given to phishing scammers. Depending on what was leaked, students users may need to change passwords, cancel credit cards, or take other actions using a non-compromised computer. Using the same device may open users to the risk of a freshly installed keylogger, which can record the new password as well.

- Run anti-virus software and consider restoring the original operating hardware. Do not trust free anti-virus programs. They can be malware in disguise. Those who aren’t tech savvy are advised to take the infected computer to a professional who specializes in malware removal.

- Contact credit agencies to report any possibilities of identity theft. Reaching out to one of the three credit bureaus sounds the alarm to potential creditors.

Above all, while canceling credit cards and changing passwords are headaches, the ultimate nightmare is catching an encrypting virus such as the notorious ransomware Locky. These awful bugs lock up files on the computer and demand a fee to release them. Some versions may be removable without paying the attacker, while others destroy the data while removing the virus. Eric Geier of PCWorld breaks Ransomware into three categories: scareware, lock-screen viruses, and the “really nasty stuff:”

- Scareware often looks like antivirus software, detecting a whole host of issues, then asking for payment to fix them.

- The FBI example above is an example of a lock-screen virus. These full-page windows prevent any computer usage and require money to remove.

- The last category, the “really nasty stuff” holds all of the files on a computer hostage.

In sum, phishing attacks range from poorly written emails to complex, well-targeted letters. Phishing attempts typically leave clues like mismatched URLs, misleading domain names, oddly placed logos, unrecognizable sources, or unsophisticated grammar.

When in doubt, do not click!